Today a special event was held today at Brookwood Military Cemetery to honour

EDITA (Edith) SEDLÁKOVÁ (nee HERMANNOVÁ), Women’s Auxiliary Air Force: Aircraftwoman Ist Class, Wireless Operator Service No. 2148430: The celebrations during 2020, recalling the Czechoslovak forces arriving in Britain eighty years ago and the seventy fifth anniversary since the end of the war highlighted a vital missing link. Whilst the Czechoslovak military commemoration chain extends over the length and breadth of Great Britain, Edith Sedláková, who lost her life whilst a member of the Armed Forces has no formal military headstone. A plaque has been put on the civilian plot where Edith is buried, but this falls far short of being honoured in the same way as her brothers in arms.

The Memorial Association for Free Czechoslovak Veterans has worked with His Excellency Ambassador Libor Sečka and Defence Attaché Colonel Jiří Niedoba to commemorate her formally at the national monument, Brookwood. The project has been complex, in reconciling British military protocols, extant since the war, with Czech military law drawn up in more recent times. The path was, however, cleared with the Ministry of Defence in Prague for a formal request to be made to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to place a Czechoslovak military headstone at the National Memorial in her honour.

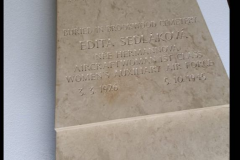

The Association is now delighted to announce the application has been successful. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is to arrange for this most historically important marker to be provided. As the only Czechoslovak women to lose her life in the United Kingdom whilst in military service it honours her personally but will also remind future generations that many Czech and Slovak women served in the British Armed Forces with courage and distinction.

A brief history of Edith illustrates her courage and sense of duty which she always showed in her journey through life.

Edith, born Edita Hermannová on 3 March 1926 in Pilsen grew up as a child of the war and its hardships. Despite suffering the consequences that befell her country, she always showed extraordinary courage and determination to face adversity in the hope that there was a better place. Family life even received a shattering blow during peacetime with her father’s death when she was only eight years old. It left her mother to look after the family, which subsequently meant making decisions about the future that must have been unimaginably difficult for everyone.

The signposts of history that came during the mobilisation of the Czechoslovak army in 1938 followed by the events leading up to Munich and Appeasement were unwelcome portents of disaster. One escape route from the fears that befell many households became a possibility. Nicholas Winton started his daring scheme to save at least some children from the grimness that seemed an inevitable consequence if Czechoslovakia came to be occupied by the Nazis.

Mindful of the dangers, the Hermann family took the ultimate step during 1939, before the occupation that year. First Edith’s brother was sent to England by the route famously to become known as the ‘Winton Kindertransport’. Then, at the age of thirteen, Edith followed and started her journey from the highly charged and emotive atmosphere of Wilson Station in Prague as children were separated from their parents, many who would never see them again.

Once in England, a new life began with foster parents and an education at Bunce Court School, Otterden, Kent that promised a more settled future. The boarding school, in the idyllic setting of the North Downs, could at least offer some respite from all the uncertainties that had affected Edith until then.

However, even the peace of that landscape ended abruptly as the Battle of Britain began, much of which then took place in the skies above the Weald of Kent. As a result, the establishment was moved at very short notice to Trench Hall, Wem in Shropshire, a traumatic experience for the children. Together with the blackout and rationing these were all harsh reminders of the cruel times they were living through.

After leaving school, however, Edith showed a resilience in her character by playing an active part in the war effort. For a short time she worked as a seamstress in a Utility Dress Factory. Famous for carrying the ‘CC41’ label and designed by some of the country’s most illustrious couturiers, the scheme worked to provide clothes made to national standard and ensure the conservation of scarce resources, as well as being affordable.

As soon as she was 17, Edith was able to join the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force on 11 October 1943. She trained as a ground based wireless operator attaining the rank of Leading Aircraft Women First Class. Her bilingual skills led to an operational posting on 9 August 1944 with 311 Czechoslovak Squadron. Originally formed as a bomber unit, by that time it was undertaking Coastal Command duties, particularly to hunt enemy submarines which still threatened allied shipping.

Her RAF record shows service at Predannak, Cornwall; Tain in Scotland and Manston. A romance flourished when she met Flight Sergeant Zdeňek Sedlák of 311, a flight engineer, and they were married at Holborn Registry Office, London on 14 May 1945. The marriage certificate records that the witnesses were Edward Hrabak, A Czechoslovak boxing champion serving in the Czechoslovak Army (Buried at Brookwood Veterans Cemetery) and Warrant Officer Josef Putna RAFVR. Then, with the end of the war in Europe, the repatriation of Czechoslovaks to their homeland began. In anticipation of returning soon, Edith applied for release from the WAAF and the date formally set for the 14 November 1945.

Arrangements were made for her to fly back to Ruzyně Airport, Prague on 4 October 1945 from Blackbushe airfield, near Camberley in Surrey. Adding to that momentous occasion, her husband was on the flight deck of the Liberator aircraft due to make the journey. These planes had been flown by 311 Czechoslovak Squadron’s Coastal Command duties. However, after August 1945 their role changed and the squadron’s operational base transferred from Manston to Prague. Now, under the umbrella of Transport Command, the squadron had begun the task of ferrying Czechoslovak nationals, equipment and supplies back to their country. For the purposes of that peacetime role, the interior of the aircraft was modified with temporary wooden flooring over what had been the bomb bay doors and wooden bench seats added.

So it was in that very spartan cabin arrangement that Edith took her place. But after three attempts to take off, the flight suffered delays because of engine problems. Eventually its journey rescheduled for the following day.

On what was to be a very special day, Edith then heard the devastating news that her allotted seat on the aircraft had been cancelled. Apart from the disappointing prospect of not returning with her husband, another compelling reason not to miss the flight may have caused her subsequent action. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a meeting was to take place with her brother at Prague airport. Whilst serving with the Czechoslovak Independent Armoured Brigade he had been granted leave, not only to welcome Edith, but explain what had happened to the family during the war. Also it was hoped that when things settled down Edith would help to restore the family glassware business.

Edith chose to make it to Prague. How it could have happened will never really be known, but she boarded the flight. The Liberator finally took off on the day, 5 October 1945, in good weather at 12.43 hours. There must have been a moment of relief and excitement as passengers reflected that their next steps would be on homeland soil. Those feelings were short lived and after only three minutes into the flight the plane began to make its way back to the airfield. Ominously, a fire had started in one of the engines.

The pilot’s desperate attempts to retrieve the situation at high speed, low altitude and tanks filled with aviation fuel for, what was then a three hour flight, sealed the fate of those on board. The plane crashed at Elvetham two kilometres east of Hartley Witney, Hampshire. The impact caused a massive explosion which sent debris over a wide area. A subsequent inquiry found the following chain of events led up to the crash.

During take-off, a petrol pipe feeding the port inner engine ruptured and fuel ignited in the engine nacelle. It seems probable that the co-pilot operated the wrong fire extinguisher but at this critical stage of flight, the pilot was unable to control the aircraft and, although it became airborne, it crashed out of control and was gutted by fire. Checks after the accident revealed that the aircraft had been very poorly maintained with little attention to the daily maintenance and servicing requirements.

All those officially recorded on the passenger manifest and crew perished, making the casualty role twenty two. It took a while before it became evident that there were, in fact, twenty three on board. The crew were buried at Brookwood in the military section and eventually honoured with formal Czechoslovak military headstones clustered around the national war memorial. In view of the problems and delays in identifying Edith as a passenger, she was buried nearby at the civilian cemetery in a communal grave, along with the many others who were on the aircraft and included several children. The accident sent shock waves through the Czechoslovak community and repatriation by air ceased as a result of that catastrophic event.

The MAFCSV together with H.E. Czech Ambassador Libor Sečka, H.E. Slovak Ambassador Róbert Ondrjcsák, the Czech Defence Attaché Colonel Jiří Niedoba and Slovak Defence Attaché Colonel Vladimír Stolárik and Edith’s family, all came to lay flowers and wreaths and see their new joint headstone.